Some technologies can go further by automatically alerting people who have been in close proximity to a patient and thus may need to get tested or go into isolation. Digital contact tracing may also jog fuzzy memories by dredging up relevant information on where a patient has been, and with whom.

However, while these methods can extinguish the first spark or the last embers of an epidemic, they’re no good in the wildfire stage, when the caseload expands exponentially. Such legwork has helped to control other infectiousdisease outbreaks, such as syphilis in the United States and Ebola in West Africa. Traditionally, tracers would ask newly diagnosed patients to list the people they’d spent time with recently, then ask those people to provide contacts of their own.

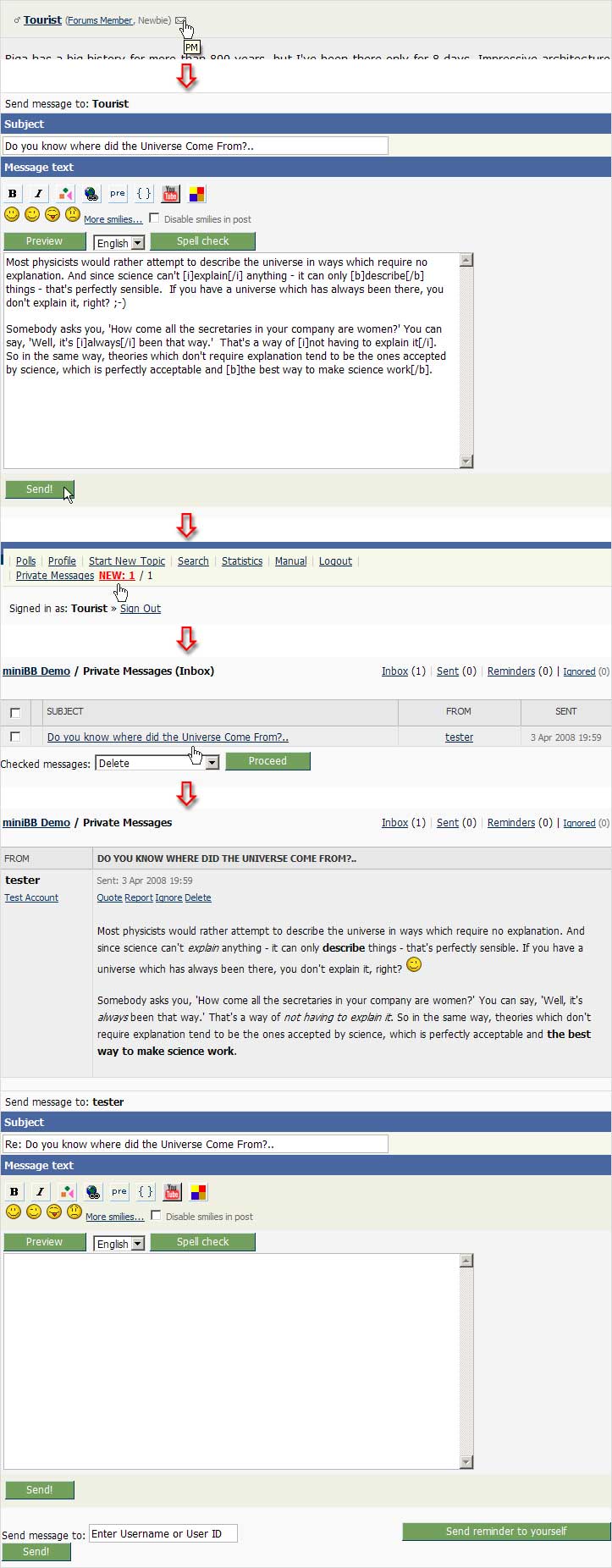

Private contact manual#

“And even manual contact tracing is very limited here-we need whatever tool we can get right now to curb our epidemic.” “Right now, in Arizona, we’re in the full-blown pandemic phase,” Beamer said, speaking in June, well before the new-case count had peaked. But that caveat has not stopped national governments and local communities from using the apps. Beamer, an associate professor of public health at the University of Arizona, was helping to test a mobile app that would notify users if they crossed paths with confirmed COVID-19 patients.Ī number of such “ contact tracing” apps have recently had their trials by fire, and many of the developers readily admit that the technology has not yet proven that it can slow the spread of the virus. In June, as the coronavirus swept across the United States, Paloma Beamer spent hours each day helping her university plan for a September reopening.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)